Perched on tables and chairs, we assembled around the perimeter of the classroom, wondering what it was. Or at least what it was for. In a clearing on the carpet was a pyre of sun bleached sugar paper, wool and wire, egg boxes, jar lids and cardboard tubes. Whispered theories passed behind hands cupped to ears. Were we having a bonfire? Was Alan being sacrificed having been caught stealing books from the library? Had someone done this mess and we’d been hauled for interrogation and the culprit weeded out? Maybe also Alan? But there was to be no kindergarten kangaroo court, no burning of a bespectacled book thief. Much to the disappointment of the baying crowd. We were all being entered into an art competition for the Eisteddfod and the brief was ‘Y Bwystfil Coll’ (The Lost Monster). Before the teachers had finished their instructions and sanctioned an ordered procession to the pyre of trash, Alan was off. Their blunder was the bugle call of ‘you can only use what’s in this pile’ and Alan was up and over the top, leading the Charge of the Shitebrigade. I remained where I was, glued to my stool by timidity, watching the volley and thunder of snatching and screaming through the battery smoke of the battlefield. Through the sundered classroom, the kids reeled and peeled away, carrying their plunder to their tables. When peace finally broke out, I made my way across a battlefield, scarred by shot and shell, to see what remained. To gather in the disparate fragments of my unmade monster.

A glass jar

Two Robinsons jam jar lids

A tangled mess of red wool

A dimpled styrofoam tray to protect cantaloupes in transit.

These were the found bones of my lost monster. I would build it and later it would win the competition, moving from classroom carpet to the exhibition walls of the local library.

But it was the glass jar that had no place on my monster that would be the making of me, rather than the medal awarded to me. There was something captivating and pure about it. A sense of potential in its transparency and the space within it. There was an awkwardness of limb and language that put me at odds with the unhindered fluidity of the world around me. A balance of being only came when pen touched paper; the transfer of imagination from ethereal signal to tangible print. Things made sense and I made sense as the empty jar filled with scraps of stories, displacing the emptiness within it and me. The lost and found.

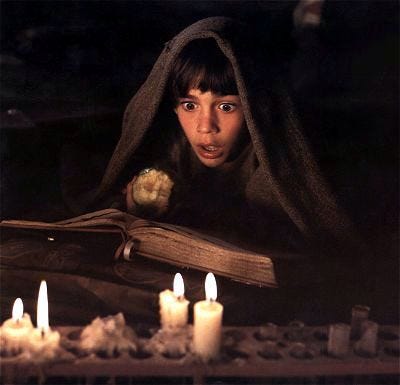

Wolfgang Petersen’s adaptation of Michael End’s The NeverEnding Story was a seminal cinematic moment for me. It centred on ten-year-old Bastian Bux, a boy shipwrecked by the loss of his mother, a neglectful father and gaggle of street kid bullies. Fleeing the latter on his way to school, he finds solace in an old bookstore owned by the acerbic Mr Coreander and is introduced to a book called ‘The NeverEnding Story’, one that Coreander deems unsafe for him to read. Bux, precursor of Alan, liberates the book, and holes up in the safety of an attic in his school. Here, hidden in the roof space, Bux finds himself drawn further and further into the world of the story, the boundaries between real life and fantasy coalescing. The film culminates with Bux having to make a choice; to acknowledge the appeals of a character that he is part of the story and can save the world within it, or deny that this is possible and allow ‘Nothing’ to end it. Unlike my passive approach to creating a monster, Bux takes a more forthright tack and destroys the one that threatens to end his story. Here was a boy who was utterly lost and adrift but found salvation in the act of reading.

The word ‘lost’ is one that is synonymous with the arts, such as reading or music. An immersion that heralds the blank verse of a lost paradise. But is it the right word? ‘Lost’ implies to be directionless, of ruination and the unrecoverable. If anything, such immersion provides direction, and one that lies in stark contrast to disorientation we feel in the world outside the medium. Even in the eye of escapism is the need to find something that we perceive as lost. Is it not the reason that we delve between pages and notes, to seek the solace of direction? To find what escapes us? It is here that we find truths, connections through time and space, fragments of ourselves. We are not lost here. We are found.

But perhaps there is an element of being lost when it comes to immersion in art. That we are lost to those who observe us at peace. The closed mouth and open eyes of the reader; the open mouth and closed eyes of the singer, semiotics of a spellbound distance that puts us temporarily beyond reach. A transitory bereavement. Our husks remain, but the heavy seeds of our spirit are winnowed and away somewhere that others can’t fathom.

Perhaps the use of the word ‘lost’ in this context was conceived to project it as something harmful, something that disorientated. The age-old notion that creativity is contrarian and corrosive, pulls at the neat structures of moral and societal fabric, warping its neat encompassing shape. Something that opposes and challenges the established norms that time and tradition have solidified. To the established order, such creative immersion creates an opposing pressure that displaces the sanctity of the traditional. A notion that creativity culls the customary

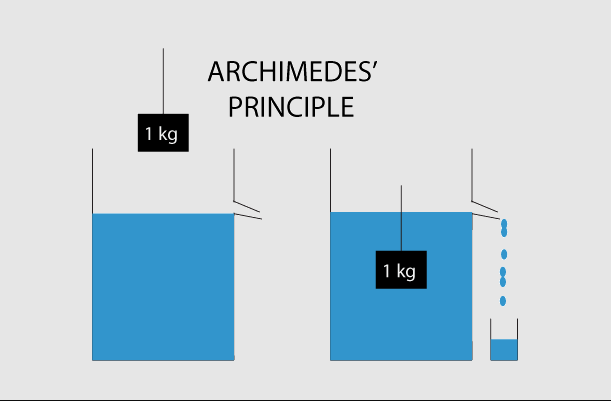

Any new shoots of creative change have always heralded loud recriminations of loss. As ‘Burner-phone’ displaces ‘brabble’ from its space in the dictionary, there is a perception that creative evolution brings not extension to the established but extinction. That the buoyant new compresses what precedes it, displaces it, spills it over the sides and confines it to being wiped away.

Whenever I have ventured to the mountains alone, holed up in a library to write or curled up to read, I have always felt that these acts of creative solitude were seen as an ostentatious shunning of society’s hospitality. But just as a seed must be sown in soil to break from its shell, creative practices also need certain conditions to secede restriction and flourish.

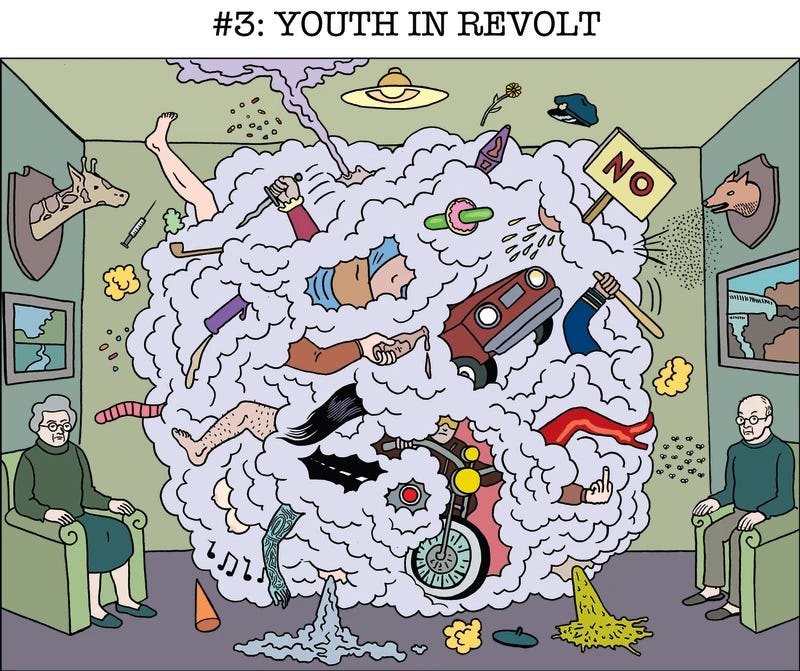

In the 1970’s, Wigan Pier became the seedbed for the working class lost in ‘blind-alley jobs’, left cold by the fallow shadowlands of manufactured pop and catalogue clothing. The youth of the industrial towns of the North turned to talc and the torch songs of lost love. It was these that brought motion and illumination, backdrop and spin turning the lost into the found. They were not lost in the music but loss existed. Free form of limb and creative expression spun the youth out from the grip of national and local control.

In the dark and dust of these dance floors, society’s shackles of conformity were lost. Through the twisted wheel of education and employment, society had told the youth that progress lay in homogeneity; that any deviation was destructive, self-absorbed and would result in personal ridicule. But now, here, those tenets were lost and the youth peeled from the straight-jackets of self-consciousness and danced upon them.

They were free and they had found their rhythms, their place, their true selves. From Punk to New Romantic, Acid House Raver to Mod, their immersion in creative pursuits were not signifiers of being lost but of being found.

It is this liberty in creative expression, through the loss of inhibitions, that fascinates me. During a recent walk along a coastal path, the tide had receded and on the edge of the mudflats stood an elderly woman facing outward into the estuary. Her eyes were closed and she moved gracefully from one shape into another as if drawing an unseen language in the sand before her. Passers-by nudged each other, reached into pockets for phones and took photos of this strange enigma, lost to some foreign land of experience. She was anything but lost.

The ability to immerse yourself in a creative act with such brakes-off commitment, and a public one at that, is something that I find so powerful. From the choreography of the ‘Dying Swan’ , Aldous Harding’s untamed rendition of ‘Horizon’ to the classroom choir singing Björk’s ‘Jóga’ it is evident that there is so much to be found from the loss of creative inhibition.

If I stand at the window of the classroom where I now teach and narrow my eyes enough, I can just about see the room where I made ‘The Lost Monster’ all those years ago. And it suddenly strikes me, that in the space and time between then and now, that I became that Lost Monster; a ragged creation of disparate pieces that would fall apart at times and be lost. But, as I bring this piece about being lost to a close, I can’t help but feel that my sense of place and purpose are now slowly being found.

For my next vacation, I want to live in your head for a week.

Holy shit can you write. There wasn't a single sentence that didn't feel delightful on my tongue. Plus a well rounded essay that tied itself up so neatly - i love the essays that invite you for a wander but place you carefully back from where you came.