Yr Ochr Arall / The Other Side

Gwendolen pulled the blanket close to her and held it in place with her chin, keeping the warmth within and the creeping cold of the world out. The night would bring with it unwelcome visitors in the form of questions, snapshots of the past and visions of the future. They appeared like badgers, creeping around in the darkness before bearing their vicious teeth when light stunned them. She felt the cold on her face and it chilled her throat as she drew in breath and she worried about the boys upstairs and hoped their faces and toes were not cold as they peeked from the polar ends of their blankets. If the cold only permeated as far as her skin then the guilt of turning off the heating seeped heavy and dark to her core and settled in her marrow. Its weight seemed to send her deeper into the sand, where checking bank balances were avoided at all costs and letters left glued shut and mosacing the hallway. The oil level sensor that was plugged into the kitchen wall had become her biggest foe.

Like the decreasing bars of phone signal as you travelled further off grid, so the bars on the sensor had fallen too. From four to three to two and then its small aerial had begun flashing red and she had barricaded it in behind the tin of tea bags. When the boys went to bed and Gwendolyn turned off all the lights, even flicking the switches of empty sockets, it would rhythmically illuminate corners and surfaces the colour of red before plunging them back into darkness. It was a beacon of despair rather than hope; a cadenced glinting that reminded her of the fragility of their situation. There was a human and financial cost to keeping it on and it would be easier to just turn it off but there was a perverse comfort to its pervasive company.

Its pulsing red glow recast the kitchen as a right atrium and living room the left. Sometimes Gwen moved it into the living room, plugging it beneath the dresser right in front of her. Here the metrical beat of its glow made the living room womb-like but rather than a safe harbour, it brought pangs of fear and dread and threat. But these were jolts that she sought. She had felt so numb as if all of her senses had fled the war within her through shelled synapses, leaving her feeling that she was observing life through a thick pane of glass. It separated her from her life and there were even times when she looked at her sons, knew who they were and what they were, but felt as if she were watching them on film. But the light, the light, would be the painful pinpricks that reminded her that she was here. Fearful but here. And she was somehow grateful for it and reliant on it.

In the indent of the cushion beside her, sat a nest of paperwork. There were forms she’d picked up from the open evening, advising her how to apply for free school meals and access grants for the boys’ school uniform. When she’d seen them on the reception table, she had taken a momentary pause, pretending to check her pockets for her keys and once she knew the coast was clear, she’d snatched at them and slid them into her bag with the deftness of a pickpocket. Gwendolyn had always been reluctant to show any semblance of struggle and caged it behind what seemed to others a hard headed pride. For her, being seen picking up those forms would have been like holding up a white flag, admitting that this was something she couldn’t do alone. Behind the bolted door of their home, she had started filling in the forms for the free lunches but the idea that her sons would be categorised, entered on some designated spreadsheets had raised the pen from the page before names were complete or boxes ticked.

She remembered her own experience of this; of having to say at the canteen tills that she was on the free school meals list. She remembered the impatient jostling of the big kids backing up behind her as she tried to whisper her eligibility to the dinner ladies. Whispers that were more like mimes were rendered inaudible by the baying crowd at her back and the timidity of the movements of her lips. She dreaded the ‘what?’ and the repeated cost of the items and the upturned open palm waiting for the money she didn’t have. She didn’t want this for them and hoped that things had moved on; that systems were automated, their cause flagged in small print on the screen and a warm nod that acknowledged them and sent them on their way.

Gwendolyn raised a corner of one of the forms and from beneath it lifted a school portrait of the boys. It was encased in an ash grey cardboard frame, embossed gold lines sweeping around its perimeter and the word ‘Tempest’ deep-set in the bottom right corner. The boys were blunt fringed and their staged smiles showed matching missing teeth. They were holding hands and the rigidity of their hands and looseness of their connection suggested that this was an action imposed on them rather than naturally occurring. Dylan’s hair and uniform were meticulous and Gwendolyn remembered him wearing his coat that morning to do his teeth to avoid the possessive stains of toothpaste splashing on his sweater. He had walked to school pulling down the corners of his hood to keep his hair away from the ruffling fingers of the wind, despite it being a still spring morning. The expression on his face told her exactly what he was thinking in that bulb flash of a moment. She knew he would have been trying to grasp the inner workings of the camera pointing at him; how a copy of his face could leap through the air into the camera and twist its way down a cable to the screen of a computer.

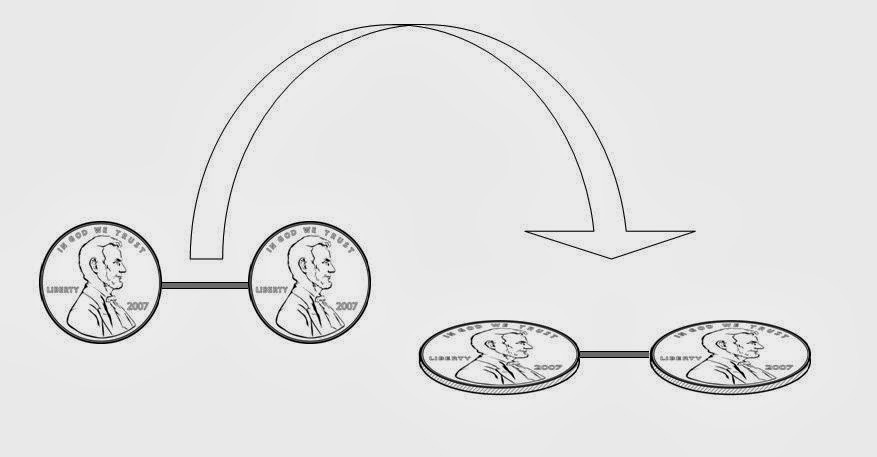

If his uncertainty made his chest draw back like a concave spoon, Cadfan was convex; shoulders back and chest pushed forward with bullish confidence. One leaf of his t-shirt collar spilled over the neck of his sweatshirt like a forked tongue and Gwendolyn had cursed when the photo had arrived home, wondering why the photographer hadn’t seen it and asked him to tuck it back in. At the underside of his left cuff, she could see a translucent path cast from wiping his nose. This specific detail coupled with the homemade haircut was something that he’d become conscious of as he’d grown and Gwendolyn would often find the photo turned towards the wall. It became an unspoken, almost daily game between them; Cadfan would turn his old self to face the past and Gwendolyn would turn it back to the present. It was always done with good humour, where one would rotate it on leaving the room without breaking stride, prompting the other to leap from the sofa and turn it back.

She saw so much of herself in him; the uncertainty of self hidden behind layers of self-sufficiency and at times, cold detachment. But despite their similarity, or perhaps in spite of it, he had always gravitated towards his father. He looked at his father in a different way to her. With her, it was with a look of familiarity; of love but familiarity. But with his father, it was with this wide eyed awe; of someone he knew had depths beyond those he could see. Once, when they had all reached the peak of Mynydd Perfedd, two ramblers had told the boys how impressed they were that five year olds had managed to summit the mountain. They had hammed it up, pretending to consult their guidebooks that the twin’s achievement was a world record and promising to phone the long dead Norris McWhirter when they got back to the car where they had signal. Whereas Dylan beamed at this, taking a bow and already imagining telling his teacher tomorrow, Cadfan’s first reaction was to point to his father and proudly proclaim ‘Well my Dad can count to 24’. The adults had all laughed, which neither boy could understand, and the hikers once again turned to their book and announced that there were three record breakers in the family now.

It was a pattern she saw repeated in school; the parents evenings where Cadfan’s teachers would say ‘he’s told me about when his dad..’ or his proud boasts to friends as they branched off at the gates at the end of the school day. But with his father’s leaving, this had stopped. The word ‘Dad’ had become a word he could not say and did not want to hear. He would recoil, looking for a reason to leave a room at home or the classroom at school if he heard it. His teacher had called Gwendolyn to share her concerns and they had both tried to talk to him about it but he had countered it with immediate demands to go to the toilet.

It was as if he could sense the word was coming, or a conversation about his father was about to unfold, and he feared it and could not be in the same space as it. But Gwen had heard him in the depths of the night, talking to his father. Rather than imagined discussions, they were replications of conversations they had had; instructions on how to get tents pegs to pull guy lines taut; explaining the route from Bristly Ridge down to Bwlch Tryfan using coffee beans on a map; mocking his father about his ‘old man y-fronts’ or his aversion to all talk of ghosts. Gwendolyn had always stayed in her room when she had been awoken by these conversations, feeling that if this was his way of connecting, of understanding , of grieving, then she could not take the risk of a wrong step on the landing alerting him that his clandestine communions were unearthed.

As time had passed, she had noticed patterns in these exchanges between Dylan and his Father. If he came home from school agitated, yet reluctant to share the cause of it, then it would be almost a certainty that once all three were in bed and an hour of silence had descended on the house, that the whispering would begin. Hearing her son’s hushed conversations with his dead father brought her hands to prayer, the peaks of her fingers resting between her closed eyes as if summoning the weight of the world to hold her in position and stop her from running and holding him. There were other nights when the conversations were audible, almost loud, spoken above the waves of his bedsheets. It was these occasions that she knew he was asleep and meeting his father in some heartbroken yet unbroken dreams. There was an odd comfort to these conversations in the sense that they were unrestrained, unfiltered by embarrassment and a need to conceal, where he spoke openly to a vision of his father rather than the still-aired, empty darkness beneath his duvet.

She leaned her head backwards so that it rested on the back of the sofa and pulled her fingers across the gloss surface of the portrait at her side. Her lips parted and released the words that seemed to press so heavily on her chest, seemed so restless at the end of her tongue until she was alone.

‘Pam nes di hwn? Pam nes di hwn i ni? Iddyn nhw?’

She spoke them heavenwards, punctuating the sentence with a deep exhalation as if this updraught would carry them further. As if they would be carried beyond the eaves, up over the quarry’s shelves, across Llyn y Cwn and traverse their way along the hinterland of Nant Ffrancon Pass to the headland of Porth Neigwl before sinking. They were questions that were more saline than the seas they landed in and more cutting and cold than the winds that carried them. They were questions that she knew the answers to but could fathom nonetheless.